| |

|

By Jared A. Davis

L. Frank Baum was born on May 15th in Chittenango, New York, in 1856. He was born with a heart condition, in which his weak heart did not receive enough oxygen and the sufferer receives chest pains.

About 1861, the family moved to a farm north of Syracuse, New York. Because of the abundance of roses it was dubbed "Roselawn." It was here that Frank (as he preferred to be called) became interested in agriculture, mainly raising chickens, and perhaps tending plants. He learned to read from his private tutor and read novels, but "demanded fairy tales."

About 1868, Frank was declared well enough to go to a boarding school, so Frank was sent to Peekskill Academy. Frank disliked Peekskill. The schedules were too overbearing, and he wasn’t military-minded. The treatment of students who made offenses was quite brutal. After two years of Peekskill, his parents, for unknown reasons, pulled Frank from school.

Once on a business trip to Syracuse, Frank observed a printing press in action. Frank admired it and wanted a press of his own. For his 14th birthday (1870) his father gave him a foot pedal powered Novelty press. Soon, Frank started his own newspaper, The Roselawn Home Journal, with his little brother, Harry, as well as making signs, stationery, and other print materials for sale. Three years later, Frank bought a new press and began The Empire and The Stamp Collector, for philatelists like himself.

However, later in the 1870’s he gave up the printing industry and began to raise small chickens called Hamburgs. He began a new magazine called The Poultry Record. Excerpts from this magazine composed his first book, The Book of Hamburgs.

On the edge of becoming an adult, Frank had a new interest: theatre! As with all his interests, he studied it earnestly. His father gave a line of theatres, but his only success was a goof-up in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. So he switched to variety shows, but his biggest success was in 1881, with his musical The Maid of Arran based on William Black’s The Maid of Thule. Changing the setting from Scotland to Ireland, the play was Frank’s first produced, and the only one in which he wrote the music for the songs.

While the show was in the off season, Frank attended a party hosted by his sister, Harriet, who wanted him to meet a girl named Maud Gage, daughter of Matilda Joslyn Gage, a friend of Women’s Rights suffragist Susan B. Anthony. Frank was assured that he would love Maud. Sure enough, his humorous reply was “consider yourself loved, Miss Gage.” Her remark was “Thank you, Mr. Baum. That’s a promise. Please see that you live up to it.” In 1882, Frank proposed to Maud. She said yes. In November, they were married.

The newly-weds did not settle at first. They traveled with The Maid of Arran, which had gone on tour. That is, until Maud became pregnant. Frank and Maud rented a house in Syracuse. After writing and producing more unsuccessful plays, Frank managed the Baum’s Castorine firm and sold his father’s axle grease while traveling.

In 1883, Maud gave birth to Frank Joslyn Baum. Three years later, they had their second son, Robert Stanton, when The Book of Hamburgs was published. The next year, Benjamin Baum, Frank’s father, died, but this was just the first in a series of events that left Frank without a job. It was time to move on.

The family moved to Aberdeen, in Dakota Territory, after Frank had taken some lovely pictures of the area. He began a store and an amateur theatre group. In 1889, Frank was forced to charge people money for the goods he had given them, and soon after, Maud had another son, Harry Neal. In 1890, Frank founded a newspaper, The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer, after his store closed. This newspaper informed the people of Aberdeen of what was going on in the nation, as well as local news, as well as Frank’s first newspaper serial Our Landlady, telling of Mrs. Bilikins, and her views on what went on the world. 1891 was the Baums’ last year in Aberdeen. Maud had another son, Kenneth Gage, and Frank lost the newspaper.

In a few months, the family moved to Chicago, the Windy City, drawn by the Chicago World’s Fair that would occur in 1893. Frank had a job reporting for a newspaper, but the pay was unbelievably low, so after a cut in his salary, he got another job, buying crockery for a department store; but he soon graduated to selling crockery on the road for Pitkin & Brooks, a china company. Being a creative salesman, as well as a popular one, he showed and taught his customers how to decorate their windows and stores, such as making a man with metal objects for a hardware store.

The Baum family was able to attend the World’s Fair, titled the World Columbian Exposition, nicknamed “The White City,” in 1983. In 1985, they moved to a new house, where, on winter nights, probably when Frank was off the road, he would tell neighborhood children, as well as his own, stories and Mother Goose rhymes, where some of the stories derived from, explaining some of the rhymes. Matilda Gage, Maud’s mother, suggested that Frank write down his stories, and try to get them published. Mother Goose in Prose was published in 1897, and the next year, Matilda died.

Because of chest pains, Frank quit traveling and began publishing The Show Window, a magazine to tell storeowners how to decorate their stores. In 1900, selections from this made up the book The Art of Decorating Dry Goods Windows and Interiors.

In 1898, Frank published his book By the Candelabra’s Glare, and did the printing himself! “I am under obligations to Mr. A.H. Dwight, of the Dwight Brothers Paper Company, for the Paper on which these pages are printed, to Mr. Chauncey L. Williams for the end papers; to Mr. H.C. Maley, of the Illinois engraving company, for the zinc etchings; to Mr. Will A. Grant of Marsh and Grant, for the inks and sundry favors, and to Mr. George R. Smith, of The American Type Founding Company, for the types and press,” wrote Frank in the volume of poetry. One of the illustrators was a William Wallace Denslow. Frank had written some rhymes, short poems, and jingles, and Denslow illustrated these. They sent them to the George M. Hill Company, who published the book Father Goose, His Book on the condition that Frank and Denslow paid half the cost of printing. The money wasn’t wasted. It sold 75,000 copies in 1899, and went into the second printing the next month.

With the money earned, the Baums bought a large cottage that they named “The Sign of The Goose,” in Macatawa Park, Michigan to live in during summer.

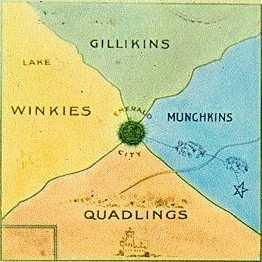

Meanwhile, Frank was working on another book. It would be a novel for children, about a girl who was carried to a fantasyland by a cyclone. It was published in 1900, as The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Frank did not realize that he was successful with this book, until December, when Maud needed money for Christmas presents. He went to George Hill who gave him the money that Frank was owed. Frank did not look at it until Maud showed it to him after he got home. The check was for $3,432.64, a whopping amount at that time. That year he also published A New Wonderland; a book he’d written some time ago, The Navy Alphabet and The Army Alphabet, and The Songs of Father Goose; a selection of Father Goose rhymes with music by Alberta N. P. Hall and new pictures by Denslow.

Considering their success, Frank and Denslow began to work on a musical. They called it The Octopus, and their friend, Paul Tietjens (a composer), wrote the music. However, when The Octopus was given to theater managers, it didn’t grab them. Denslow had all the time thought that The Wonderful Wizard of Oz would make a good play, and after The Octopus’ flop, Frank wrote a version that stuck closely to the book. After it was marked “NO GOOD,” it was transformed into a full-load musical comedy! Believe it or not, the theater managers liked it! Of course, the director, Fred Hamlin, and his friend, Julian Mitchell, heavily revised it. The show was first produced in 1902, with Anna Laughlin as the adult Dorothy, Fred Stone as the floppy Scarecrow, and David Montgomery as the piccolo-playing Tin Woodman. Read a summary with Baum's songs.

1901 was Frank’s big year, trying to equal The Wonderful Wizard of Oz’s success, with Dot and Tot of Merryland, The Master Key (a teenager’s science fiction novel), and American Fairy Tales, a collection of short stories Frank published in newspapers. However, Dot and Tot was Frank and Denslow’s last collaboration. It is suspected that they separated over a controversy on the Wizard of Oz play.

As it turned out, Oz, the book and play, had won Frank’s fame for good, and he was deluged with requests for a sequel. Frank didn’t want to write sequels, for fear of always doing the same thing. In 1902, Frank offered The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus, Santa’s biography. In 1903, came yet another attempt to leave Oz: The Enchanted Island of Yew. A publisher, Reilly & Britton, offered to make a second Oz book their flagship title. So, Frank decided to write another Oz book, but no Dorothy. The Marvelous Land of Oz was published in 1904. It was illustrated by John Rea Neill, whose style is now used among most Oz illustrators.

To help publicize the book, Frank wrote the 27-installment Queer Visitors from The Marvelous Land of Oz newspaper comic feature, illustrated crudely but humorously by Walt Mc Dougall. This was followed by The Woggle-Bug Book: The Unique Adventures of the Woggle-Bug, illustrated by Ike Morgan. Baum used this short picture book and Marvelous Land to write another play, The Woggle-Bug, with music by Fredric Chapin. Because of bad reviews, it closed in a year. The Queer Visitors series was quite interesting. Whereas The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was a story about a girl from America coming to a fairyland and finding many surprises, this series was about characters from a fantasy land coming to America and finding many surprises that we take (or took) for granted. This is obviously Baum's attempt to show that there is wonder and "magic" (like electricity, telegraphs, and even magnets) in the real world.

The sales allowed Frank and Maud to enjoy a luxurious tour to San Diego, California, where they stayed at the Hotel del Coronado. Frank wrote several books in the large, accommodating hotel.

1905 was Frank’s year for serializing. His Queen Zixi of Ix was serialized in St. Nicholas magazine; his Animal Fairy Tales were in The Delineator, not forgetting that Queer Visitors was in its second year. 1906, John Dough and the Cherub was published. Frank was beginning several series that he used pseudonyms, or pen names, instead of his real name. Names like Laura Bancroft, John Estes Cooke, Schulyer Stanton, Capt. Hugh Fitzgerald, and Edith Van Dyne were among his many names.

1906, Frank and Maud sailed to Africa, where they saw a family who had crossed a desert; Roman ruins; mummy cases, 12th century books, pyramids, the Sphinx, and a wedding in Cairo, Egypt. They even saw Mt. Vesuvius erupt. However, Frank said that the Statue of Liberty was the most beautiful thing he’d seen on the trip.

1907, Frank published another Oz book, Ozma of Oz, and this time, Dorothy returns! Neill again returned to illustrate the book, as he did all of the rest of Baum’s Reilly & Britton books that he used his real name on. Frank had made an agreement to continue the Oz series for at least four more books. In 1908, Frank published Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, and Frank Joslyn married and had a son!

Frank was inspired to create The Fairylogue and Radio-Plays, a multimedia show that had live actors, photograph slides, colored films, and live music. The titles were The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, (to show that it was based on the book, not the play) The Land of Oz, (to differentiate from The Woggle-Bug) Ozma of Oz, John Dough and the Cherub, and a slide-only show was Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz. Touring through several states, the money to present such a show ran out, the show closed in New York, and Frank was out of money.

In 1909, Frank, trying to get out of debt, turned the rights to the books that the Fairylogue series were based on over to the Selig Polyscope Company, who made them in the films for Fairylogue first place. Frank made a salary agreement with Reilly & Britton, who published The Road to Oz that year. In 1910, Frank published The Emerald City of Oz, which, he hoped, would be the last Oz book. Maud and Frank had long since sold their Macatawa Park home. Maud used her own money to help build a new permanent home in a quiet little town near Los Angeles, California, called Hollywood. They named their new home “Ozcot.” Frank realized his agricultural ambitions here, by raising chickens, as well as flowers and other plants.

In 1911, to finally eliminate debt, Frank filed for bankruptcy. (He was not actually out of money, because all of the royalties for his Reilly & Britton titles went straight to Maud.) He published the “Trot and Cap’n Bill Books,” The Sea Fairies (1911) and Sky Island (1912), but these were unsuccessful. So, Frank gave in to eager fans and for 1913, he published The Patchwork Girl of Oz and the six “Little Wizard Stories” picture books.

Frank decided to write a new musical, so, in March (likely to capitalize on the re-launching of the Oz series), The Tik-Tok Man of Oz opened, loosely based on Ozma of Oz. But those terrible critics compared it unfairly with The Wizard of Oz play. The play closed in summer, while the show was still in the black. The story was reused for Tik-Tok of Oz, the Oz book for 1914.

1914 marked the year that Hollywood was hit by the motion picture industry. Frank founded a new club of athletic gentlemen called the Uplifters, and together they performed Frank’s new plays. Soon they began movies! The Oz Film Manufacturing Company owned a seven-acre lot for filming. Their first films were The Patchwork Girl of Oz, The Magic Cloak of Oz (based on Queen Zixi of Ix), and His Majesty, the Scarecrow of Oz, whose the story was used for The Scarecrow of Oz, the Oz book for 1915. The book featured Trot and Cap’n Bill, from The Sea Fairies and Sky Island, who move to Oz. Paramount and the Alliance Film Corporation released the Oz films. After a series of shorts, and two films for adult interest, the Company folded and sold to Universal.

Frank’s health was getting worse, but he kept on writing. A brief conflict occurred in 1915, when Reilly & Britton published The Oz Toy Book. They hadn’t consulted Frank and it was quickly taken out of print. This book almost made Baum demand that Neill no longer illustrate his books, as he felt they were not the right style for his books. He preferred cartoonish look of artists like Denslow over Neill's elegant style. Reilly & Britton asked Neill to make his pictures look more humorous. Obviously, he did so: after some more Oz books, the quality of his art slowly began to decline. In the end, Baum finally reconciled himself with the fact that Neill was his illustrator, and even invited Neill to visit him at Ozcot, a visit that sadly never occured.

His Oz book for 1916, Rinkitink in Oz, was just a revision of an unpublished manuscript. He just made Dorothy and the Wizard rescue the heroes. His Oz book for 1917 was a little more original, The Lost Princess of Oz, in which Princess Ozma is kidnapped. Frank had his gallbladder removed in 1918. He put two manuscripts for Oz books in a safety deposit box, to be printed just in case anything happened to him. That year he was able to have The Tin Woodman of Oz printed.

World War I had begun the previous year. Frank Joslyn and Robert were serving as an officer of heavy artillery and an officer in the Engineer Corps. Because of the War and many misconceptions, Frank had even revised one of pseudonymous books to describe the horrors of war, taking all glory and glamour from it.

Frank revised his two Oz book manuscripts, to match his the rest of the series. The war did end by the end of 1918. But by 1919, Frank was getting very ill, so ill that a nurse had to stay at Ozcot. Whenever he was well enough to do anything, he was courting Maud, or revising a book. But May 5th, 1919, ended all of that. Frank had a stroke, and after a few encouraging words to Maud, he slipped into a coma, only to awake for a few seconds the next day to say “Now we can cross the Shifting Sands.” He then died.

He was buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Park. The Magic of Oz was published that year. The next year, 1920, when women were allowed to vote, Glinda of Oz was printed. Reilly & Britton, who had now become Reilly & Lee, decided to continue the Oz series, so Maud approved Ruth Plumly Thompson to continue the Oz series, then John R. Neill was the next “Royal Historian,” then Jack Snow, Rachel Cosgrove, and Eloise Jarvis McGraw and Lauren McGraw. Perhaps because of their contributions, (which kept Oz in the public eye until MGM made their WIZARD OF OZ film) Frank’s books live on.

SOURCES: Study of my own, most learned from L. Frank Baum: Royal Historian of Oz by Angelica Shirley Carpenter and Jean Shirley, © 1992. Other materials include the works of L. Frank Baum, Eric Gjovaag's online FAQ, Michael Patrick Hearn's The Annotated Wizard of Oz, Katherine M. Rogers' L. Frank Baum, The Creator Of Oz, and John Fricke's 100 Years of Oz.